This is the first part of Wunderdog’s Design Sprint e-book. Get the entire e-book as a pdf here.

Part 1: What is a design sprint?

If you’re following the field of technology or regularly meeting people who work in start-ups, you may have heard of the Design Sprint approach. A fast-forward product development process originally made famous by GV (Google Ventures), Design Sprints are gaining popularity — and it’s no wonder. Players in an increasing number of fields are interested in discovering alternative ways of launching the design process to ensure that the product or service is viable. Meanwhile, those with more extensive experience might use the week of design thinking for discovering new prospects for a service that’s nearing the end of its life cycle.

Written by GV alumnus and creator of Design Sprint, Jake Knapp, the book Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days offers a diverse and illuminative introduction and playbook to the subject. The web is also full of step-by-step guides on how to run your design sprint. This is not one of those. This is an overview of what a design sprint is, what it is good for and what it’s not for.

All innovators and entrepreneurs know how tempting it is to just become complacent with your own idea: when all the pieces seem to come together seamlessly, it can be hard to challenge your own train of thought. You may even spend a long time on the later development stages, and it’s not until the first negative user feedback or the unexpectedly low sales that make you realize what’s really going on.

This is exactly what the Design Sprint is for: get to know the actual users before getting too far ahead with the design and development process. You might call it a sneak peek into the future: Does the concept have that certain something? How are the end users reacting to the concept? Even superficial user research will help you decide whether you should actually commit to the costly development process.

The structure of a sprint

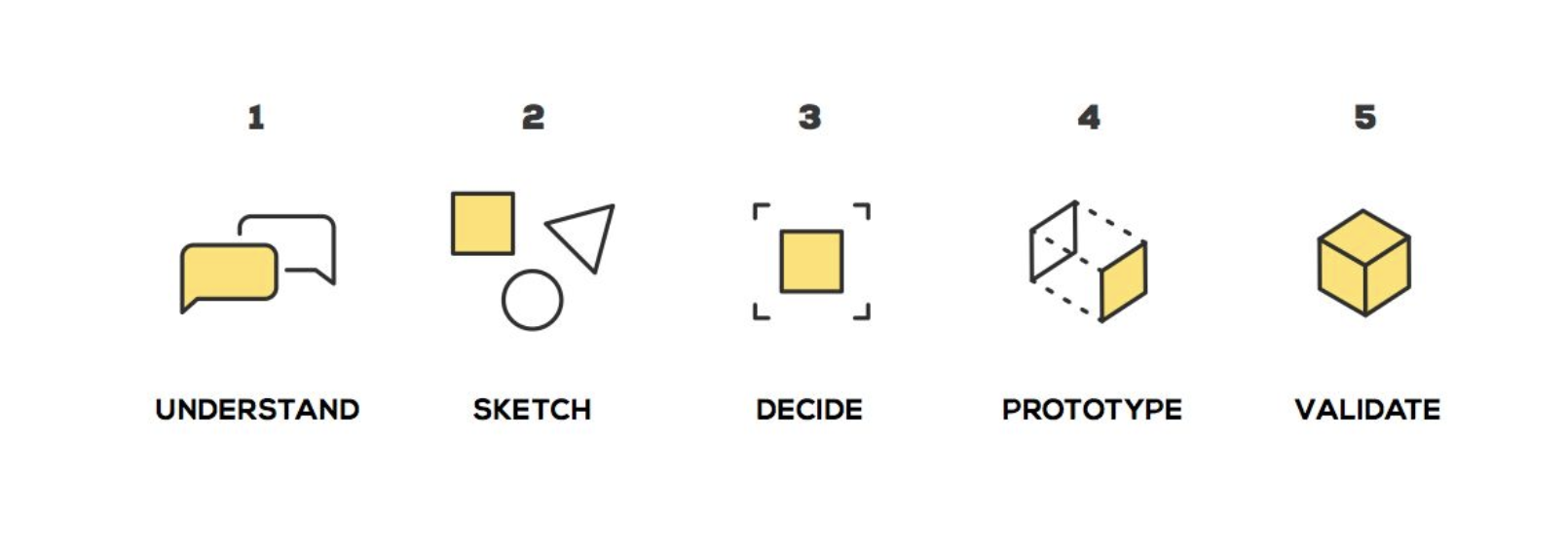

A typical Design Sprint can be divided into five stages

1. Understand

A typical Design Sprint begins with a facilitator who will help you map the problem or subject area. It may be a good idea to illustrate the discussion with notes and drawings that you place on the wall: illustrating the discussion will create a collective memory that can be made more complete as the week progresses. In Design Sprint this process is described as “How Might We” note-taking.

2. Sketch

Once the subject area has been sufficiently charted and the challenge to be tackled has been decided, it’s time to start preparing potential solutions. Solutions can be of any level — from abstract high-level process maps to tangible UI details. The most productive approach is usually to begin with independent brainstorming and then bring the results together afterwards. The grouped results can then be refined further, either in teams or individually, depending on the situation.

3. Decide

Select one or more of the solutions for prototyping.

4. Prototype

Build a prototype of the selected solution(s). The format and look of the prototype varies a lot case-by-case: a simple line drawing, a realistic digital service, a model to demonstrate scale, an actual physical product similar to the real thing, a staged/acted service scenario… The prototype is simply a facade; there’s no need for it to function as a real product. The point of the sprint is to create a facade with minimum effort, but make it realistic enough to allow your team to validate the hypothesis or solution you have specified together.

5. Validate

In the last stage, you test the prototype with real end users. Testing can take place on many different levels. You should select the testing method based on your field and hypothesis.

A typical way would be to create a simulation of the situation of use and then monitor how the users react, either through discussions or by watching the situation. If the prototype seems unfinished, it can be more viable to use it as a basis for joint development and discussions and see where the users take the discussions.

A Design Sprint always ends with a summary and a conclusion: you decide if you want to continue with the concept, suspend the idea or go back to the drawing board. At Wunderdog, we encourage you to do this immediately after the sprint. It’s always your decision, however, and sometimes it’s best to let your company discuss the situation and mull things over.

When we run Design Sprints with our customers the sprint team comprises a facilitator who is usually accompanied by another designer. A technical expert may be necessary if the objective is to specify roadmap for a digital service. From your, the customer side, we are accompanied by a team of 3–5 people: a decider, who is usually the C-level exec with enough power to make business decisions. A separate product owner or project manager should be included if the decider is not one of them. Other people present should be people responsible for the practical implementation of the project. To ensure sufficient efficiency, the people from your side should be expected to commit to the sprint for two entire days.

Find Design Sprint part 2 here.

How we design Design Sprints at Wunderdog?

Our experience of various customer cases has allowed us to tailor the approach to Design Sprints depending on customer needs. Groups of end users are at the heart of our Design Sprint method, but we have also r epeatedly observed the importance of two dimensions:

1. Applying the structure in the customer’s own context

2. Communication: participation, discussion and the tone of the discussion.

Application

The discussion on product design methods is often focused on how strictly the “original” pattern should be followed. Frameworks, such as Lean Startup, Scrum and Design Sprint, are applied both very strictly and very freely depending on who is using them. There are different sides to all approaches. To ensure success, it’s essential that the focus is moved from the approach to the matter at hand. Achieving this becomes easier if those managing the process are sufficiently familiar with the method. Wunderdog has achieved great results with Design Sprints through a strict application of the Google Ventures model but also with more free approaches.

We have carried out most Design Sprints with a more free approach, as the context, goals, and extent of the cases have varied significantly. At the same time, we have noticed that along with providing a great tool for turning ideas to products, Design Sprints can be used to gain a better understanding of an unclear subject area or even to clarify the business idea of a company (see the examples below).

Participation

If the goal is to use a Design Sprint for purposes other than clarifying and validating an idea, you are going to need a bigger team and more time. As a result, your company will have a more extensive understanding of the subject and experience of the working method. Larger teams should be divided into an active team and a commenting team, and the latter can be expected to invest less time in the process.

Discussion

Even though a week is a short time to reach decisions and get things done, discussions are a valuable method for fostering learning and understanding, and you should always ensure there’s enough time for them.

Tone of Discussion

To ensure that we gain results from a Design Sprint, the atmosphere should be curious, open, safe and confidential. According to a study by Google concerning design teams in general, the dependability of the team members and the psychological safety of the group are some of the most essential features of the teams with the best results. In addition, the Design Sprint team needs to achieve the right atmosphere in a very limited time. This is actually one of the greatest challenges in a Design Sprint. The participants often have extensive experience in their respective fields. It may take courage to let go of the safety of your expertise when usually it’s precisely the expertise you need to demonstrate to your customers and colleagues. However, for the duration of the sprint, you should be prepared to let go of the idea that you can predict things based on your previous knowledge.

Understanding users, summarising the findings and using them as a basis for further ideas require sensitivity. It is possible to misinterpret the reactions of users and reject observations that are based on intuition. However, it only takes a little effort from the team to reach a confidential, open way of communicating. This kind of atmosphere makes it easier to apply information, make rapid changes to plans and view things in a completely new light.